Blog

Fractional Exhaled CO, A State-Of-The-Art for Early COPD Detection?

- by Mohamed Al-Sabri & Hithesh K. Gatty

- 4 Feb 2026

What is exhaled CO and why does it matter?

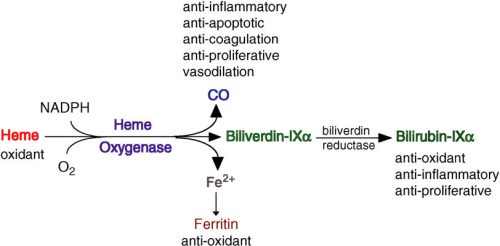

Exhaled carbon monoxide, usually written as eCO, is the small amount of CO that leaves the body with every breath. Part of this comes from external sources such as tobacco smoke, and part is produced endogenously when heme is broken down by heme oxygenase1 during oxidative stress and inflammation. When the airways are irritated by smoke or other noxious exposures, expression of heme oxygenase1 increases, and this can lead to higher eCO levels. eCO is therefore a signal that integrates smoke exposure and inflammatory activity in the airways.

What is Fractional exhaled CO (FeCO) measurement?

To ensure pinpoint accuracy, the FeCO test follows a standardized “10-second” protocol similar to the gold-standard FeNO test. The patient exhales steadily for 10 seconds, but the device specifically captures and analyzes the air from only the last 3 seconds of that breath.

This precision method is critical because it bypasses the “dead space” air in the mouth and throat, instead sampling the end-tidal air from deep within the lungs. By isolating this final portion of the breath, clinicians can filter out environmental noise and obtain a pure reading of the HO-1 enzyme activity, providing a true reflection of the body’s internal oxidative stress and airway inflammation.

A signal with significant clinical value

One of the most robust clinical applications of eCO is as an objective marker of recent smoking. Healthy nonsmokers typically have very low eCO, whereas daily smokers show clearly higher values reflecting their recent smoke intake. This difference is strong enough that breath CO measurement has become a standard component of many smoking cessation services to verify abstinence and detect ongoing smoking.

In COPD and other smoking-related airway diseases, eCO can add further insight. People with COPD have higher mean eCO than healthy nonsmokers, and in several studies, smokers with COPD have shown higher eCO than smokers without COPD, consistent with greater airway inflammation and oxidative stress. Elevated eCO has been associated with worse airflow limitation and may track exacerbation-prone phenotypes in some cohorts, although findings are not fully uniform across all studies.

When eCO is followed over time, it can help to:

- Distinguish smokers from nonsmokers and validate self-reported abstinence in cessation programmes.

- Highlight individuals whose combination of smoking exposure and airway inflammation may put them at higher risk of developing COPD or of faster disease progression.

- Monitor how the lungs respond when someone stops smoking or initiates new therapies, as falling eCO generally reflects reduced smoke exposure and, in some settings, reduced airway inflammation.

Why eCO is becoming state of the art in COPD monitoring

As respiratory care shifts from hospital-centred models toward community, primary care and remote monitoring approaches, there is a growing demand for tools that are noninvasive, low-burden, and repeatable in everyday settings. Ideal tests for early COPD and risk stratification should be comfortable, sensitive to early changes, and easy to integrate into digital care pathways.

eCO matches this profile well. It is measured with a controlled exhalation into a handheld sensor, provides a result within seconds, and can be repeated frequently without discomfort. Because it reflects both recent smoke exposure and aspects of airway oxidative stress, eCO is increasingly used as:

- A point-of-care biomarker in smoking cessation services (with a 4week quit commonly validated at CO < 10 ppm in UK programmes).

- A support tool in COPD risk assessment, especially in current or recent smokers whose spirometry is borderline but whose inflammatory burden may be high.

Crucially, eCO complements rather than competes with spirometry. Spirometry captures the mechanical side of lung health, such as forced expiratory volume and vital capacity, while eCO reflects biochemical processes related to oxidative stress and inflammation that may precede irreversible structural damage. Used together, they provide a more forward-looking picture of lung health and risk.

Spiroluft, bringing eCO and spirometry together in one device

This is precisely the gap that GattyInstruments AB aims to close with Spiroluft, a new portable respiratory analyser that integrates advanced spirometry with exhaled gas sensing in a single platform. The Spiroluft concept builds on a high-resolution flow sensor for spirometry combined with additional sensor channels for breathborne signals, all connected to a mobile client for real-time visualisation.

Spiroluft is designed around three core signals captured in one controlled breath:

- Spirometry, to quantify airflow obstruction and track lung function longitudinally.

- Exhaled CO (eCO), to capture smoking exposure and airway oxidative stress in the same maneuver.

By combining these signals in a portable device, SpiroLuft can support:

- Earlier identification of COPD risk in current and former smokers, especially when spirometry alone is near the diagnostic thresholds.

- Self-monitoring of lung health for smokers and ex-smokers, with immediate feedback as eCO falls when smoke exposure decreases.

- More informed follow-up in established COPD, using trends in both lung function and eCO to highlight individuals drifting into higher-risk trajectories

Spiroluft is built to connect with digital, AI-enabled platforms so that measurements can be securely uploaded, analysed, and visualised over time. This enables remote monitoring models where clinicians can view dashboards of lung function, eCO, and symptoms, and where smart algorithms can help flag patients who might need earlier review or adjustment of their treatment, helping to shift COPD care from reactive crisis management to proactive, data-informed prevention and monitoring.

Reference

[1] Carpagnano, G. E., Resta, O., Foschino-Barbaro, M. P., Gramiccioni, E., & Barnes, P.J. (2003). Increased inflammatory markers in the exhaled breath condensate of cigarette smokers. European Respiratory Journal, 21(4), 589-593. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.03.00022203

[2] Slebos, D. J., Ryter, S. W., & Choi, A. M. K. (2003). Heme oxygenase-1 and carbon monoxide in pulmonary medicine. Respiratory Research, 4, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-4-7

[3] Jarvis, M. J., Russell, M. A. H., & Saloojee, Y. (1980). Expired air carbon monoxide: A simple breath test of tobacco smoke intake. British Medical Journal (BMJ), 281(6238), 484–485. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.281.6238.484

[4] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2008). PH10 Stop smoking services, evidence review (CO validation at 4 weeks). (PDF). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng209/evidence/ph10-stop-smoking-services-february-2008-pdf-10892313614

[5] Montuschi, P., Kharitonov, S. A., & Barnes, P. J. (2001). Exhaled carbon monoxide and nitric oxide in COPD. Chest, 120(2), 496–501. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.120.2.496

[6] Gatty Instruments AB (2025). https://gattyinstruments.com/

[7] SPIROLUFT: A Next Generation Breath Analyser Utilising Simultaneous Spirometry & Pulse Oximetry, Säfström, Felix, Master thesis, Uppsala University, Sweden https://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1916914/FULLTEXT01.pdf

[8] The Role of Heme Oxygenase-1 in Pulmonary Disease, Laura E Fredenburgh, Mark A Perrella, S. Alex Mitsialis, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital; and Division of Newborn Medicine, Children’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Degradation-of-heme-by-HO-1-HO-1-catalyzes-heme-degradation-to-biliverdin-IX-CO-and_fig1_6812848

[1] Carpagnano, G. E., Resta, O., Foschino-Barbaro, M. P., Gramiccioni, E., & Barnes, P.J. (2003). Increased inflammatory markers in the exhaled breath condensate of cigarette smokers. European Respiratory Journal, 21(4), 589-593. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.03.00022203

[2] Slebos, D. J., Ryter, S. W., & Choi, A. M. K. (2003). Heme oxygenase-1 and carbon monoxide in pulmonary medicine. Respiratory Research, 4, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-4-7

[3] Jarvis, M. J., Russell, M. A. H., & Saloojee, Y. (1980). Expired air carbon monoxide: A simple breath test of tobacco smoke intake. British Medical Journal (BMJ), 281(6238), 484–485. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.281.6238.484

[4] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2008). PH10 Stop smoking services, evidence review (CO validation at 4 weeks). (PDF). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng209/evidence/ph10-stop-smoking-services-february-2008-pdf-10892313614

[5] Montuschi, P., Kharitonov, S. A., & Barnes, P. J. (2001). Exhaled carbon monoxide and nitric oxide in COPD. Chest, 120(2), 496–501. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.120.2.496

[6] Gatty Instruments AB (2025). https://gattyinstruments.com/

[7] SPIROLUFT: A Next Generation Breath Analyser Utilising Simultaneous Spirometry & Pulse Oximetry, Säfström, Felix, Master thesis, Uppsala University, Sweden https://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1916914/FULLTEXT01.pdf

[8] The Role of Heme Oxygenase-1 in Pulmonary Disease, Laura E Fredenburgh, Mark A Perrella, S. Alex Mitsialis, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital; and Division of Newborn Medicine, Children’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Degradation-of-heme-by-HO-1-HO-1-catalyzes-heme-degradation-to-biliverdin-IX-CO-and_fig1_6812848

Read More

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Current Status of COPD: Challenges and Advances

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Characterized by progressive airflow limitation, COPD affects an estimated 300 million people globally, with smoking and air pollution as primary risk factors.

Despite advances in healthcare, early detection remains a major challenge. Many patients are diagnosed only after significant lung damage has occurred, limiting the effectiveness of interventions. Current treatments focus on symptom management bronchodilators, inhaled corticosteroids, and pulmonary rehabilitation, but there is no cure.

Recent developments, however, offer hope. Digital health technologies, including portable spirometers and mobile respiratory monitors, are enabling continuous lung function tracking and remote monitoring. Meanwhile, research into novel therapies such as regenerative medicine, anti-inflammatory drugs, and personalized treatment strategies is expanding the potential to slow disease progression.

Public health efforts emphasizing smoking cessation, pollution control, and vaccination remain crucial. With increased awareness and integration of digital health tools, COPD management is gradually shifting from reactive care to proactive, patient-centered strategies.